|

|

|||||||

|

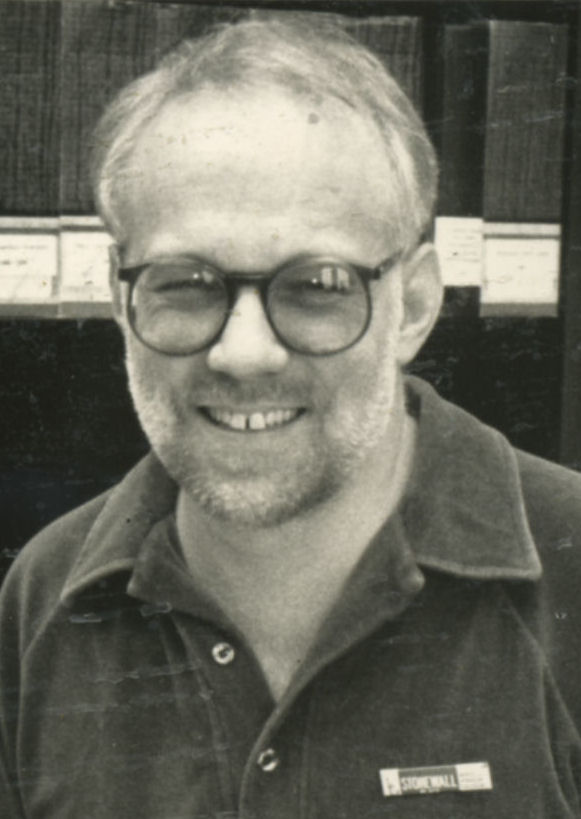

Michael Lisowski is an LGBT activist best known for producing and hosting "The Queer Program", a cable access program in Milwaukee which held live news, interview and call-in programs for the LGBTQ community for 25 years, from 1992 to 2017. He is believed to be the longest serving producer of a cable series with MATA (Milwaukee Access Telecommunications Authority). Lisowski was also a very active member of Milwaukee's LGBT community, from the Gay People's Union, to BWMT/ Black & White Men Together, and other organizations.

Lisowski was interviewed by History Project curator Michail Takach in December 2023. In the interview, Lisowski talks about GPU, BWMT, The Queer Program, as well as numerous bars he visited and people he befriended witnin the LGBT community. Interview with Michael Lisowski; December 2023 Michael Lisowski was born on the south side of Milwaukee. His family moved to the north side a year later, and he remained on the north side ever since. He went to Catholic grade school and the St. Lawrence Seminary School in Mount Calvary, Wisconsin. In 1968, he graduated from Mesmmer High School in Milwaukee. Because he left seminary after his sophomore year, he had two years to make up after high school. Michael attended UW-Milwaukee from 1970-1972, took some time off, and returned from 1977-1979, when he achieved bachelor's and master's degrees in social work. "For awhile, I tried to do some nursing," he said, "but I just could not get the chemistry or the physics. It was too out of the twilight zone for me, so I said, the heck with this!" Early years "They really keep an eye on you in the seminary," said Michael, "and I think they realized who and what I was. After my first two years, they said, hey, why don't you step out for a year or two. Socialize. Meet girls. Go on some dates. And see what happens. So I did that." "They weren't wrong," said Michael. "I started realizing when I was 12 or 13 that I was different. I definitely had some attractions. But you know, this is 1962, 1963. I always tell people that I was gay before anyone said gay. And that's true, nobody said gay until 1969, 1970. It was a difficult time for me." "There were no resources available to us at all. I had to do a term paper during my freshmen year in college. I chose to write it on homosexuality. When I went to the Milwaukee Public Library, I was surprised that the books I wanted were stored downstairs in a vault. I had to put in a special request, and they shipped them upstairs in a dumbwaiter, and then they had to be returned downstairs when I was done. These books weren't just out on the shelves for people to discover. It was like the library was ashamed of them. I will always remember feeling that I was seeing something people weren't supposed to see. The whole process was really bizarre, but I did get a good grade on the paper." Nowadays, people often have an LGBTQ family member they can relate to. But Michael was the first in his family. "There wasn't even anyone I suspected of being gay," said Michael. "I was totally isolated by myself. There was nothing on TV, nothing in the movies. I never heard any rumors about where gay people could be found. I was just so completed in the dark." "Luckily, I found a Catholic priest who I opened up to. He was very supportive and understanding. He is the one who got me through it all. I'm just lucky that priest was so helpful; at the time, it was much more likely for him to be the direct opposite. He could have just said, this is a sin, you've got to stop, because you're going to hell. But he didn't. He was young, right out of the seminary, and very open-minded. He didn't even tell my parents." Liberation now Michael has only the warmest memories of 1970s gay nightlife. "One of my friends from the seminary moved to Milwaukee, and so we decided to find some gay bars. The River Queen was one of the first bars I can actually remember going to. I remember going in, and sitting down, and trying to act casual. I didn't want anyone to see me in there. I hadn't even told my parents yet. I was scared to death, and it was the safest place for me at the time." "One night, a bunch of my coworkers went out and ended up at the same gay bar I was at, even though they weren't gay. They just happened to end up there. They were like, hey don't worry about it, you know, there's no problem. That was a huge relief to me, because now I knew I could be open with my co-workers." "I loved the Neptune Club, at the corner of Kane and Humboldt. That was a real hotspot for awhile, until suddenly, the owner decided to open up The Factory. The Factory was fantastic: they had that big demon head in the background blowing cold steam out of its mouth. So, the Factory became the place everyone went. There was a front room, and a back room, and everywhere was packed. The Factory moved a few times, but the first Factory was always the best." "I also remember the Royal Hotel, but I only went there a few times before it was torn down. There was the Baron which I always thought was the best, best place. The smaller places like C'est La Vie, Phoenix, and 219 were such a blast. You could pop in and and out and back and forth and spend the whole night on the block. And of course, there was always Your Place (YP) and This is It. There were just so many in those days. You couldn't hit them all in one night if you tried." "I remember people talking about a bathhouse on St. Paul Avenue, but I never went. We only knew where to go because other people told us. So, you had to be somewhat sociable, or you'd never find these places. Many of these places didn't really want to be found. They were happy with the regulars because strangers could be trouble. You never know what someone might do." "Back then, the only places to meet people were bars or Gay People's Union. And there wasn't any history available to us. It was like we were the first gay people that ever existed and nobody existed before us. I never heard of the Black Nite. Nobody talked about that at all. Until it was on the news two years ago, I had never heard of it. Not even Gay People's Union knew about it. I thought, my God, if this is new even to me, does anyone alive know about this?" "When I eventually told my parents, my mom said she thought so, and my dad just kind of brushed it off. You know dads, they don't always know what to say. But in the end, they were both very supportive and positive. They didn't say "you're not my son anymore," which is what I was afraid of." "Even today, there are still so many issues with people coming out. Sometimes I see LGBTQ orgs posting these extensive wish lists, and I laugh, because back in the 70s and 80s, our wish list was that we didn't want our parents to throw us out. We didn't want to be disowned. We didn't want to be beat up on the street. We didn't want people to find out we were gay at work, at school, at home." "We wished and hoped for the most basic of needs -- because not even those were guaranteed to us." Sparking a revolution Gay People's Union was going strong when Michael joined in fall 1976. "I remember calling them up and finding out about their Monday night meetings," said Michael. "I don't know if I was just looking for something more to do, or more community than I was finding in the bars, but I made some very good friends. I always considered Louis Stimac and Alyn Hess my mentors because they were the ones who really helped mold me. I got to know Si Smits, Father Joe Feldhausen, Eldon Murray, and others from way back in the day. I met Miriam Ben-Shalom, who was seen as such a rebel for fighting back against the military. Miriam and Alyn were kind of the mom and dad of the game." "I finally felt anchored and connected to something. I remember GPU had a radio program about gay topics. That was a big deal. You didn't even hear the word "gay" on the radio back then." After an especially violent police raid of the Club Baths, GPU hosted a massive demonstration after their Monday night meeting. "We marched from the Farwell Center all the way down Wisconsin Avenue," said Michael. "Some of us were holding a gay flag, and others were holding the American flag. I remember thinking, I'll hold the American flag so I appear more patriotic. You know, who's going to attack someone holding an American flag? And then my picture wound up in the local papers, right next to Alyn Hess." That protest really fired up the community. For months afterwards, GPU meetings were standing room only. Michael considered Louis Stimac, one of the GPU founders, to be one of his very best friends. "He was so knowledgeable about everything, but also so down to earth and so practical. He was a really good resource for the community. He was also a former seminary student but wound up being a social worker for the county and state. But Louis found himself forced out of a job he loved because he was gay. That's what sparked his activism." "It's funny, right? If they had just kept their mouths shut and left us alone to do what we wanted to do, we would never have become activists. Their actions kicked us right out of the closet, so to speak, and now they had to deal with our rage." "I'd always be going over to his house. First he lived on Van Buren near Ogden, and later to a duplex on West Michigan Street. Two gay guys lived upstairs, and Louis lived downstairs, with roommates constantly coming and going. He was always taking in people who needed a place to stay. And he loved to cook, especially for Christmas. He would be cooking for three days in advance! And the thing was, you could just go over to Louis's house and stay as long as you wanted, and he'd have food, and drink, and refreshments. It became a place to spend the holidays if you weren't welcome at home. Back then, you couldn't bring your boyfriends to holiday dinners or talk about gay stuff with your family. Louis made sure everyone had a gay holiday!" Sadly, Louis was diagnosed with throat cancer and died in April 1994. "Here's this guy, who loved cooking and eating so much, and then he was unable to eat solid food at the end of his life," said Michael. "It would have been ironic if it hadn't been so traumatic." "Louis also had a remarkable collection of gay films on videotape. Near the end of his life, he decided to erase or tape over most of them – especially the adult films – for some reason. And I remember thinking, if someone had saved all of those, they would have been such an incredible historical archive of that time." Justice for all At first, everyone was together in Gay People's Union, but over time, the community splintered into different subgroups based on causes and interests. Sports organizations. Theater organizations. Senior organizations. Youth organizations. Women's organizations. "Over time, Gay People's Union did its job of advancing the community, but it was a victim of its own success," said Michael. One of those organizations was Black and White Men Together, founded in San Francisco in 1980. Soon, chapters quickly popped up all over the country, including Milwaukee. "I was going out with black guys at the time, and there were four or five white guys I knew that were really into black guys. I knew a couple from the bars who started hosting meetings at their home around 40th and Locust Streets. Later, we moved to a house on 15th and Vine. The monthly meetings would be 15-20 minutes of business and the rest was all socializing and sweet talk." Over time, BWMT blossomed into a real activist organization that hosted conventions around the country. "This was important work," said Michael. "Gay bars were not always very welcoming to black men. Some bars tried everything to keep black men out: you need to have multiple forms of ID, you need to have specific forms of ID, you need to pay a higher cover charge, you can't come in because we don't know you. And then the bartenders would tell people they needed to spend more money. You can't just have a Coke, you need to order drinks or leave. And then the DJs would change the music if they noticed a lot of black people dancing. It was just blatant." "So, we set up these strategies where we'd go to a certain bar and test how they treated a white couple vs. a black couple. We presented the results to the bar owners and asked them to do better. We raised a lot of awareness about discrimination at the door. Of course, then the bars came up with memberships, and that allowed them to keep out anyone who didn't get a membership." "I served on the national committee for many years, but eventually I vacated my post. I believe the organization is still together in some manner." Although BWMT was a groundbreaking way of confronting gay racism, and celebrating interracial relationships, the organization was overshadowed by two 1985 tragedies. First, the AIDS crisis began to seriously impact Wisconsin with 100 confirmed cases, and second, the murder of Delbert Pascarvis shattered the local BWMT chapter. Delbert, as the BWMT Milwaukee president, had just won an award at the BWMT National Convention. He was strangled to death in his Booth Street home only days after coming home. Gay People's Union was overshadowed by AIDS too. "Bill Meunier and Si Smits raised money to keep the hotline running for several years," said Michael. "But Gay People's Union was like a nuclear family: the parents raise the children, and then the children grow up, move out, and start families of their own. That's what happened with Gay People's Union. It was like the great grandfather of everyone. Every gay organization in Milwaukee that exists today can trace its roots back to GPU." "Nowadays, you've got people in this community who take credit for everything, whether they were involved or not. And then there's the GPU generation, who did so much for so many, and their names are barely even remembered today." Protecting the next generation "While I was attending UWM, I became aware of a gay support group on campus," said Michael. "You didn't see a lot of gay support in 1979. There were no "safe spaces" in schools back then." "Since I was pursuing a social work degree, the program leaders invited me to join. After running the program for a year or so, they were now graduating and leaving Milwaukee. I hated to see this program end, so I decided to step in. The meetings were at the UWM Union every other Saturday at the time. Eventually, one of the students suggested that we move to the Milwaukee Central Library, so I reached out and secured a free meeting room for us. We stayed there for over 10 years. I'm still not sure how students found out about the program. Sometimes, 15-20 kids would show up, other times one person would show up. Sometimes nobody!" "It was a true peer-to-peer support group and I think it did a lot of good. We created a youth resource list that outlined restaurants, bookstores, and other welcoming spaces. We'd do presentations at schools, libraries and community centers. Thanks to a grant from Diverse and Resilient, we were able to launch a toll-free peer support hotline in 1996. We operated two phone lines out of an upstairs room at the BESTD Clinic. The operators were pure peer counselors, not certified or trained counselors. Eventually, everyone figured out we were running this hotline on Fridays and Saturdays, and kids would show up at the clinic to hang out during hotline hours." "Eventually, two of our kids (Kurt Dyer and Justin Lockridge) created Project Q and moved the program to the Milwaukee LGBT Community Center. They wanted to run the program as volunteers. By that time, I'd been running this group for nearly 20 years on my own. I never made a dime on this program, but I did put a lot of my own money into it. The Center had the space, the resources, the finances, and the organization to take this to the next level. And today, Project Q is still supporting LGBTQ youth with peer-to-peer support." Adventures in broadcasting Following an anti-trust ruling, local cable operators were required to reserve free public access for the community. This created an incredible opportunity for pioneering broadcasters. Tri Cable Tonight, an award-winning news program produced by Mark Behar, ran from 1987 until 1992. "At first, you needed a whole crew to do a show: four people on audio, two people on video, and then your onscreen talent," said Michael. "So, you needed a team of people to produce a weekly show, and not everyone was willing to make that volunteer commitment." "When Tri Cable Tonight ended, MATA came up with a new, more automated format where a single person could do all the production work while they were onscreen. I thought it would be really neat to do a show like that, so I spoke with Dan Fons about getting something on the air. We'd worked together at the Milwaukee AIDS Project, and he was a bit of a rabble rouser with ACT UP at the time. And suddenly, Jeffery Dahmer happened, and everyone was wondering what was going on, and there's all this talk but very little news. Nobody knew what was real and what was rumor." "So, I said, let's start a weekly show where we can present community issues from our point of view. Let's try to get everyone on the same page about what's happening in our world. And we got The Queer Program going." "I think we got two shows on-air before the Dahmer trial began. We were pre-empted for a few weeks, but then we ran on a regular basis every Tuesday night for the next 25 years. If I had ever suspected The Queer Program would last 25 years, I would have recorded every episode. I'm glad Dan recorded so much of it. It's a shame the studio didn't preserve anything. When the studio shut down, they were going to throw out all the tapes – a whole storage room of three quarter inch tapes – and that sent me into a panic. I grabbed as many as I could and brought them home. It's not the whole series, but I took as much as I could. I plan to donate them to the UWM Archives." "Dan made the show a very activist show. We always shared the latest ACT UP activities and protests. I remember him trying to get Herb Kohl to come out of the closet. Wilson Cruz from MY SO CALLED LIFE was one of our first big-name guests. He was one of the first actors to come out at such a young age. We had Candace Gingrich, lesbian niece of that idiot Newt Gingrich. We had two gay couples from the marriage equality lawsuit." "I'd be out and about and someone would come up to me and say, "aren't you the guy that does that show?" Sometimes, they'd be straight men with their wives or girlfriends. Sometimes, they'd be shy (maybe closeted) single men. And one time, someone came up to me and asked if I had accepted Lord Jesus as my savior. Naturally, I said "oh yes, I have." "The show got a lot of prank callers, but we played along with the joke. We were always so calm, and redirected the calls back to them, and toyed with them a little. I always thought this was our chance to make them look idiotic in front of everyone for their behavior. One guy would call in, wait for us to say "hello" and then we'd hear a flushing toilet." With the show's 25th anniversary approaching, Michael got the news that the community cable contract would not be renewed and the studios would be closing. By that time, people were making their own videos on their phones. "The mindset changed: who needs community cable when you have YouTube?" said Michael. "Still, we made it to 25 years – and I am very proud to be the longest-running producer for Milwaukee Community Cable." Points to ponder Now retired, Michael is still an active community volunteer, and he's still reflecting on 50+ years of service to the local LGBTQ community. "Nowadays, you see LGBTQ and even longer acronyms. People already forget that, back then, it was just "gay." Everyone was gay together. We fought for gay rights, the gay community, gay liberation. This soon evolved into gay and lesbian, and then GLB (gay, lesbian and bisexual.) By the late 1990s, the T was added and we became LGBT. It's just how we've evolved across the generations. I'm not saying its right or its wrong – but I do worry that we've lost the togetherness. "We really don't have that united front anymore -- and that sure makes it easy for our enemies to attack us." (Interviewed by Michail Takach, December 7, 2023.) |

|

Credits: Web site concept, design, contents and arrangement by Don Schwamb.

Last updated: April-2024.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.